Alvaro Labiano is an astrophysicist who joined Telespazio UK in July 2021. He is the Support Archive Scientist of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), working as a contractor for the European Space Agency (ESA).

JWST is a NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) led mission but with significant partnership from ESA and the Canadian Space Agency.

ESA provided two out of the four instruments: the Near InfraRed SPECtrometer (NIRSpec) and the Mid InfraRed Instrument (MIRI), the latter with participation of American institutions. On JWST, Alvaro is one of the top experts of MIRI, and as such was invited to the Space Science Telescope Institute in Baltimore (USA) during 6 weeks in May/June 2022 to lead the MIRI 3D spectrograph (the MRS) team for the commissioning of this instrument.

We caught up with Alvaro for an update on the JWST since its launch in Dec 2021.

1. How many people were involved in the calibration of all the instruments on the James Webb telescope?

It is really hard to estimate. Instruments were built in the mid/late 2000's by different companies and consortia, and they had to be pre-calibrated to a certain level before delivery to NASA. As an idea, the official number of people involved in developing JWST is about 20,000. We started calibrating MIRI back in 2006 and delivered it in 2012. The MIRI Test Team was mainly composed of grad students and very young postdocs back then. Over the years, the team members have changed a lot, but the number has almost always been between 20 to 30. During commissioning we needed more hands on deck, as we had to cover 24/7 shifts on the console for 6 months, using a total of 51 people. And that is only for the science operations of MIRI, one of the four scientific instruments on JWST. Add to that the other instruments, analysts and data processors, systems and flight engineers, managers, support staff, Principal Investigators (the scientist leading the observing proposal) and NASA representatives… I think the answer can only be a lot!

2. How long did it take?

The full JWST commissioning took 6 months, and it was really a successful campaign. Now the Space Telescope Science institute (STScI) had to fine tune part of the operation modes to make sure we got the best out of each instrument. Before commissioning, of course, we had several ground calibration campaigns that lasted months, again with 24/7 shifts. Some happened during blizzards and hurricanes, creating absolute logistic nightmares… and a ton of funny anecdotes but that's a story for another time!

3. What was your role in the calibration of the MIRI instrument?

To make sure the MIRI-MRS instrument (the mid-infrared 3D spectrograph in JWST) performed as it was expected when delivered to NASA, and for launch. During the commissioning, my role was to check it was ready for science operations, and officially transfer our knowledge to NASA by June 24. I led a team of 10 scientists and engineers that had to work up to 16-hour days, including weekends for more than 3 weeks at the end of the commissioning, but we passed the science readiness review with flying colors! Of course, we hit some bumps during the campaign. The main one being that some modes of operation were too efficient. Webb worked better than expected and many of our commissioning observations were filled with background galaxies where we expected an isolated star, or several emission lines from gas in galaxies showed structure (due to different velocities in the gas) that we were not expecting to resolve.

4. How much more precise is the data obtained by MIRI and other JWST instruments compared to other instruments?

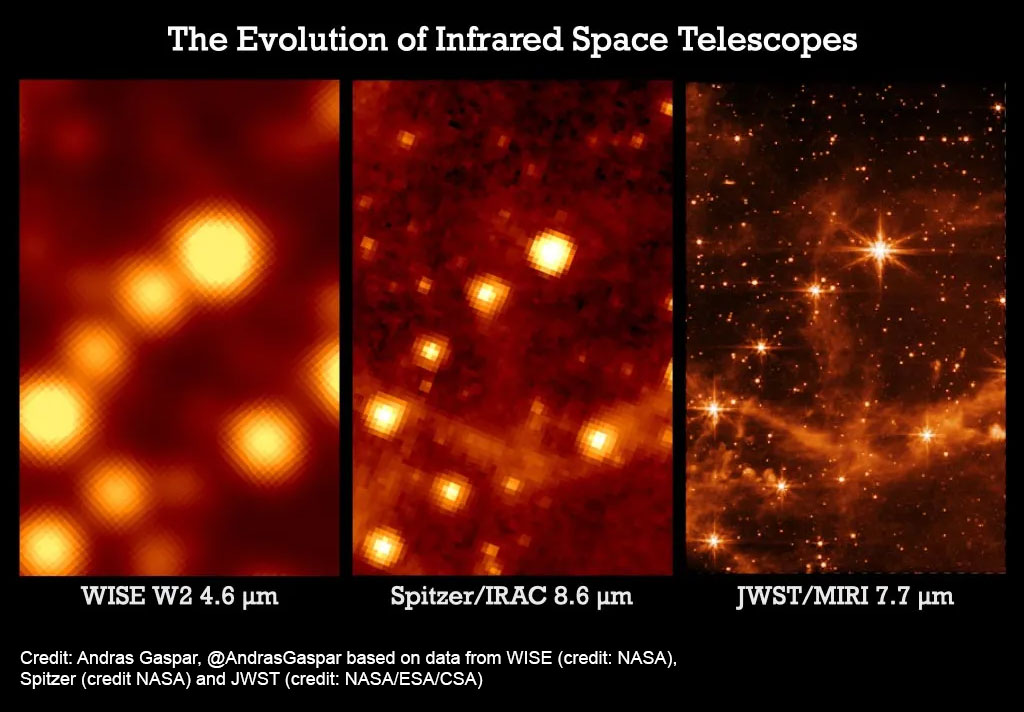

Webb is achieving spatial resolutions similar to Hubble, with a 100 times better sensitivity. This means that we can get images (and spectra) as stunning as Hubble in much less time. Compared to past space observatories in the infrared, Webb's resolution is also much better (e.g., 10 times better than Spitzer), as illustrated in the next figure. This is a comparison of three images of the same astronomical field, taken with three different infrared space telescopes at similar wavelengths.

5. Were you surprised to see the president of the USA looking at the first pictures?

Absolutely! I think we all were. It was very last-minute news that he would do it, at least for us. If understood correctly, he even stopped a meeting about the Middle East to talk about the images. We all knew that JWST was something else but we (or at least I) were not aware of the huge hype that it was creating outside the scientific community. The fact that the US president changed his agenda to basically see a picture of the sky we just took felt unreal. And it gave us a sense of how huge this mission was going to be, not just from the scientific point of view.

6. Pictures are nice, but could you explain at least the significance of one of them in simple terms?

Let's not forget that JWST has a huge responsibility to the public. NASA, and the US Congress, needed to prove that the huge budget and major delays, and controversies around Webb all these years, were worth the wait. The best way of doing it was releasing stunning pictures and comparing them with previous missions. Not only out of beauty but also the scientific implications that these have. So, the goal of these first release pictures was to prove to the community that the telescope was working as expected. They really illustrate the capabilities of JWST compared with other missions. Also, the "wow factor" played a major role when selecting the first targets to observe.

For instance, this image of the Tarantula Nebula is the latest public release from NASA. It is a mosaic of several near-infrared images taken with NIRCam, where we can see tens of thousands of young stars that were hidden in previous images. Apart from the central (blue in this image) cluster, we can see other stars mixed with the dust, bubble (empty regions), or gas cooling down (red-brownish colors) that may end up forming new stars in the future.

7. So, what is next for the JWST? What is the next big event we should look out for?

Now JWST has started scientific operations. As with other observatories, these are divided in years or cycles. Webb is currently performing observations for Cycle1, and the call for proposals for Cycle 2 will open this November. This means scientists will be able to submit their scientific programs for Cycle 2 for evaluation by STScI. If accepted, these programs will be observed along 2023-2024. This sequence repeats every year until end of mission.